When Mumbai resident Rajiv Singh, 50, got a call four-five years ago from a Gujarat-based financial agent that a significant number of shares belonging to him, his parents and his brothers were lying unclaimed, he thought it was a hoax call.

But after multiple calls and meetings, and when the consultant gave him the names of some of the shares and informed him that they had acquired substantial value now, he thought it was worth checking.

Says Singh, “We had shares of big companies like Reliance, Kotak, and Tata in the 1990s, but we lost track of them, and they got lost when we moved houses.” At the time, shares were issued as physical certificates, and the family had misplaced them over the years.

These shares belonging to Singh’s family landed in the Investors Education Protection Fund (IEPF), a repository of unclaimed shares and dividends created under the Companies Act, 1956, through a 1999 amendment.

When the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) introduced the dematerialised account system in 1996, people who had bought shares previously in the physical format were required to open demat accounts and get their shares dematerialised. The shares of all those who did not do so eventually ended up in IEPF, which stores all unclaimed shares, and not just the physical ones.

For instance, if people have stocks in demat accounts, but their bank accounts linked to the demat accounts become inoperative, then such shares also get transferred to the authority.

Investors must also update their know-your-customer (KYC) details, including home addresses and contact numbers, and collect dividends regularly to show their continued ownership of the demat account. If the proceeds are unclaimed, or KYC is not updated for seven years straight, the shares are moved to IEPF’s custody.

The values of some of these shares bought years ago, especially the physical ones, are now substantial.

“People had invested small amounts of money in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s and didn’t keep track of their investments. Their investments of Rs 10,000-15,000 have grown into crores now,” says Ankit Garg, a senior lawyer specialising in IEPF cases and founder of Delhi-based Garg Law Chambers (GLC).

According to a consultation paper published by IEPF in January 2023, it has roughly 1.17 billion (117 crore) unclaimed shares. Dividends worth Rs 5,600-5,700 crore are yet to be returned to shareholders, says Garg.

Vijai Mantri, co-founder of Jeevantika, a Mumbai-based consultancy services company, estimates that around Rs 75,000 crore worth of shares could still be in physical form.

The problem until now has been the timely recovery of these shares and their value because of the long-winding process and documentation.

In Budget 2023-24, Union Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman announced an integrated portal by IEPF to ease the reclaim process.

The process is already online and claimants must fill out an e-form (IEPF-5) to authenticate their identity with IEPF. Companies also process the forms and submit verification reports online.

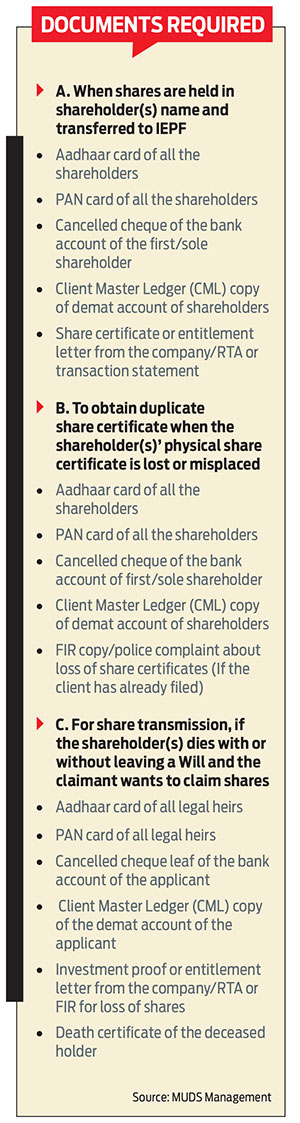

However, the claimants must submit the original documents, such as share certificates, etc., physically to the respective companies that need to be surrendered before getting the shares in demat. The IEPF consultation paper had said that it has standardised the document list and operating procedures, including for cases involving transmission and loss of share certificates for ease.

While there is little clarity on the integrated portal immediately, it is expected to help claimants track the status of their cases or companies to update their customers on their pending claims, Garg believes that it may take more than a year to create the integrated website before it goes live.

Whether the new portal will ease the process is still to be seen, but as of now, the road to recovery of these shares is full of obstructions.

Forgotten Past

Cases abound of people who have no idea that their families had bought shares in the past that are now lost or forgotten.

In some cases, the owners died without recording the details of their investments. In others, families moved cities or houses, leaving the companies without a valid address for communication and distribution of dividends etc.

The shares Delhi-based Aditya Talwar’s grandparents bought for his mother years ago are now worth a fortune. Since the 42-year-old businessman’s father had a transferable job and they often moved cities, the family had forgotten about the shares.

Says Mantri, “In 70 per cent of the cases, people lost shares because they moved houses. In those days, large migrations were common, even within cities.”

There are some firms and agents that track the owners and help them out for a fee. It was one such agent who had reached out to Singh initially. Aditya’s family was approached by Garg’s firm.

Says Mantri, “Most cases belonged to pre-2000 when many people had no demat accounts, and the shares were in the physical format, so it was difficult to track them when people moved houses.”

Ahmedabad resident Mukesh Joshi, 60, who took the help of MUDS Management, a corporate finance and legal management consultancy, to retrieve his shares, discovered that his father’s shares were in a joint name with him. He got wind of the matter when an agent called relatives in their village. They were trying to contact Mukesh’s father as he was the main shareholder. After his relatives informed him, he began the process.

In Garg’s experience, most of the active cases now are of those living in India. Many are small shareholders from small towns and cities who had invested during the stock market boom of the Harshad Mehta-era and forgot about them, he says. “People who moved abroad still have investments back home and don’t know whom to contact and are even unaware their investments were transferred to the government,” he says.

The Tough Paper Trail

Multiple rounds of documentation are required for the reclaim procedure, and it’s all about getting the papers right. That can be a tough task given that some documents may be dated, damaged or lost in case of people who are no longer alive.

Claimants must also certify credentials like bank details, signature, Aadhaar, and Permanent Account Number (PAN), and give a declaration in a bond paper to prove they were living in the previous house (whose address may be registered in the certificate), produce share certificates, and if lost, must get a duplicate one from the company.

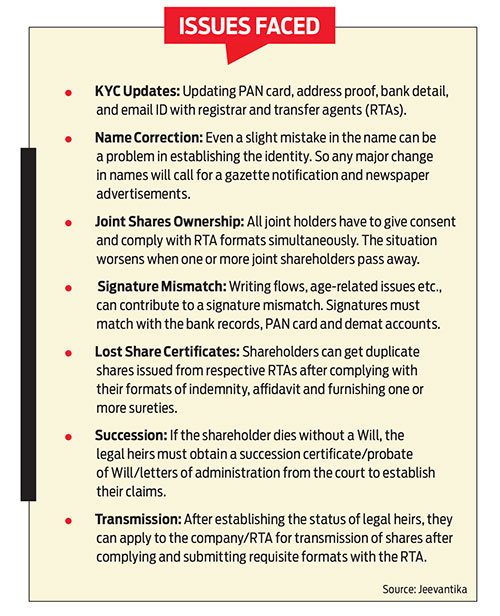

“At the time, there was no PAN or Aadhaar card, and people would sloppily put their names, typically in some variation of their first or middle names to apply for shares,” says Mantri.

Such issues of name matching can create huge documentation problems, he adds.

But, despite challenges like residence proof, as rent deeds were uncommon in those days, Mantri says people may have some forms of identification like an old bank statement, etc.

Besides, there are also succession issues to deal with. If the owner passes away, they must produce death and succession certificates. “If the share value is more than Rs 5 lakh, and there is no Will, then a succession certificate must be obtained from a court, which usually takes 3-12 months. Some people also have family disputes; for instance, some may have gone through a divorce,” says Mantri.

Shweta Gupta, founder and CEO of MUDS Management, adds that there are different scenarios for submitting documents. “If the share value per folio number per company is less than Rs 5 lakh, then a legal heir certificate, a ration card with details of all family members, and a family deed is required. If the value is more, then ‘Probate of Will’, a letter of administration or court-registered Will must be produced, subject to RTA confirmation, besides the succession certificate,” says Gupta.

The claimants must establish their credentials with the registrar and transfer agents (RTAs) to prove it is the same person or nominee, relationship with the shareholder, etc.

The RTA will also ask for an indemnity guarantee, stating that the shares do not belong to anybody else. Once satisfied, the matter goes to the share-issuing company, which examines everything again before it goes to IEPF, which approves and disburses the amount.

However, preparing these papers isn’t simple. Says Mantri, “The rules say that the client needs to get a guarantor, indemnity, and other things if the value is decent. If someone has shares worth Rs 50 lakh, then they have to get a guarantor of Rs 50 lakh till the shares are transferred in the person’s name. A normal person cannot do all these tasks, and they don’t even have the time.”

The documents the government and the company require are extensive. “There is also some element of coordinating with the companies and the company secretaries, so it is not just about dealing with the government departments,” says Talwar.

For most big companies, corporate governance and shareholder values are important, so he says the documentary requirement goes up. Moreover, from the company’s perspective, these steps are critical because that’s the only way to protect genuine shareowners.

Says Gupta, “Although the process is well-defined for all the authorities, syncing between RTA, the company, and IEPF is sometimes difficult. After verification from the RTA and the company, share recovery may take a little time to reach the shareholders’ accounts.”

Test Of Patience

The process to recover or get these physical shares and deposits re-registered can be quite exhausting.

When Singh was first approached by an agent, it proved to be the start of a long journey that took him to several professionals. “We struggled for about a year-and-a-half, and then we got somebody else to look at it. We also got one of the big companies involved, but they could not get the process closed,” says Singh, managing director at an engineering and manufacturing company.

Singh, who is Garg’s client now, believes one should be careful in choosing the professional or firm that handles the case. “At least three or four people had approached us, but we gave the job to two of them. We struggled for about two-and-a-half years, but nothing happened. You need to have a very professional approach and be relentless in your pursuit,” he says. In the last 15 months or so, with the help from Garg’s firm, he was able to clear 90 per cent of the backlog. Rajiv believes that their focused and scientific approach and understanding of the processes like what affidavits need to be made or the documents that need to be produced, have helped crack his case. The documentation complexities are such that few clients would be able to follow it up on their own without the help of a professional or firm.

Mantri says that often the cases get delayed due to the clients’ poor understanding of the processes and the lack of proper documents. “Filling out forms could be difficult even for opening a bank account, and it is much more complicated in IEPF,” he says. It can be tough for a person without solid legal or financial acumen, as they have to start from scratch, including opening a demat account, says Garg, adding, “There are cases still pending from the ’70s.”

It also gets delayed at the government’s end due to work overload. “IEPF receives 30,000-40,000 claim requests per year but is able to process only about one-third of them,” says Garg.

The government keeps records of all claims filed, both successful and rejected cases.

“Our website has compiled data on unclaimed shares so that people could search with their surnames and the state where they lived at the time. You can go to IEPF, provided we know the shares you own, or else you will keep searching from company to company,” says Mantri. The government’s integrated portal will be of help in the future.

Sometimes, the delay also happens at the end of the companies and their registrars when they do not respond on time.

“There is also the aspect of incentivising the work for a company secretary for prioritising it. Although the regulator is pushing hard, these officials are cautious as they don’t want to do something that is questionable later, given all kinds of frauds happening in the capital market. So if the value of the shares is higher, the scrutiny is tougher,” says Mantri.

In addition, companies may not have full-time staff to look into these matters.

Gupta says one must be diligent and actively follow the rules. The IEPF process is quite time-consuming and demands patience. “If the right approach is followed, the shares can be recovered quickly,” she adds.

The tunnel may be dark, but there may be a silver lining at the end of it, provided you get the paperwork right or get the right professional if you can’t do it yourself. With patience and persistence, you can reclaim what’s rightfully yours.

sanjeeb@outlookindia.com