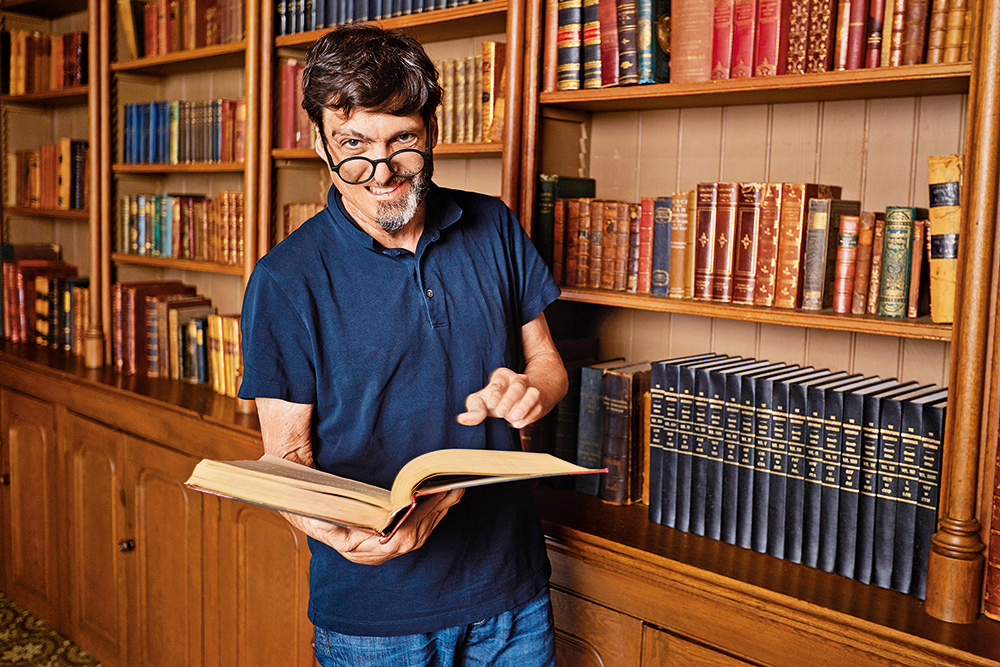

Dan Ariely, author and professor of psychology and behavioural economics, at Duke University, North Carolina, the US, studies the irrational ways in which we all behave. In his own words, he “looks at people not from a rational perspective, but from the irrational perspective. We basically ask questions around what we are doing that is not in our long-term best interest”. In an interview with Nidhi Sinha, Editor, Outlook Money, as part of the Wealth Wizards series, he talks about himself, his signature half a beard, how people can deal with irrationality, and the role of emotions like misbelief, trust, and human motivation in how people behave or make decisions. Here are the edited excerpts from the interview.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your half a beard.

My half a beard look is a little about my history, and a little bit about social science.

Many years ago, I was badly burned; about 70 per cent of my body was burnt. I spent about three years in hospital, and the right side of my face is all scars, and hair doesn’t grow on that side. But of course, I could shave, which made me look less strange. So, for many years I shaved.

Then a few years ago, I went on a month-long hike during which I didn’t shave. When the hike ended, I looked in the mirror and I didn’t like my look. But I thought I’ll keep this half a beard for a few weeks. I posted a few things on social media, and to my surprise, I got some messages from people who thanked me for my half a beard. These were people struggling with their own injuries. I was out there with my injury, and that gave them a little strength. For example, there was a woman in her 50s, who had a car accident when she was 17, and she hadn’t worn a skirt since then. She said she is going to try doing that now.

But the real interesting thing happened about four months down the line, when I felt that my relationship with my scars and injury has changed. The act of shaving, or the act of half shaving, for me, was also an act of hiding. Stopping shaving was incredibly helpful for self-acceptance.

It was also about social science. I am a social scientist, and I did not predict that stopping shaving would help with self-acceptance.

If you had asked me, how would it feel like to not shave, I may have said, on the first day, people would ask questions, point at me, kids would laugh. But if you ask me, what would be the effect four months down the road, and how would it change your self-acceptance, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you. And I think that’s what social science is supposed to do.

I couldn’t help but notice your email signature, “irrationally yours”. Do you think irrationality is so inherent that people can’t rid themselves of it?

Yes. There are two answers to this. The first is that I think about the human mind as a Swiss Army Knife (SAK). It is never the best tool but in a compact way, it does a lot of things. It’s a little knife, it’s a little can opener, it’s a little tweezer, it has little scissors.

Our mind is like that. We’re not perfect in anything, but we are quite good at a lot of things. Also, our SAK (mind) was not designed for the task of modern life. So we don’t have a tool to deal with cryptocurrency, investments, and compound interest.

The second thing is that we usually think of irrationality as bad. However, not all irrationality is bad. Love is irrational, but do we want to eradicate it? Of course, not. Many times our motivations at work are irrational. There are a lot of things that are irrational, but wonderful.

Taking a leaf from your latest book, Misbelief: What Makes Rational People Believe Irrational Things, could you help us understand how misbelief can lead to irrationality and affect investing decisions?

The overall envelope for the book is that as a society, we’re losing trust. The problem with misbelief is that it leads us to trust less. And when we trust less, society loses, and this also lowers our ability to act in our long-term best interest.

I think investing inherently requires trust. If you ask whether people are willing to put their money in a bank, open a brokerage account, invest in stocks, or just keep cash under the mattress, buy gold or cryptocurrency, one of the big issues (in decision-making) is trust. And as trust gets lower, people are less willing to do things.

I was recently in South America, where the government is trying hard to get people to save, but hasn’t been very successful. One of the blessings of modern lives is that we live much longer. But that’s also a curse. If we all worked till 65 and died at 66, we would not need to save that much money for retirement. But if we work until 65 and then we live another 20 years, that’s a substantial amount of time. That means that for every year that we work, we need to save for about half a year at retirement. That’s an amazing amount, and it’s hard to achieve that without starting early and saving in a way that gets us compound interest. So, in such a country, trust ends up being a huge barrier. The government is offering all kinds of paths for savings, but people aren’t taking them.

When we invest, we have some very bad strategies. We buy things that are expensive, we sell things that are cheap, and we are our own worst enemies. The more people engage with the idea that we would outsmart the market—I know when to buy, when to sell, I can time the market—the more they end up losing money. The stock market is a good example of a place where often our emotions get the best of us and lead us astray, both when stocks go up and down.

Cryptocurrencies are investments that are not trusted by the Indian regulators and experts. Still people rushed to invest in cryptos in 2021 when they were at all-time high levels. There’s movement in cryptos even recently. So, how does the trust factor play here?

First of all, crypto has the benefit that it’s a trustless system. The system has sufficient things that you can trust it, but you don’t need to trust anybody. And that’s the reason I don’t like it. You know, I think that we are in a crisis of trust, and I want to fix trust. And the economic system is one of the places to practice trust. Look, I wrote a cheque, and the same amount cleared. I used my credit card; it worked. If we used blockchain and cryptocurrency for everything and didn’t practice trust, we would be worse off.

But in terms of people buying cryptocurrency, there’s certainly a big notion of gambling, and as people, we are susceptible to gambling.

B.F. Skinner, the famous American psychologist, showed what he called random reinforcement. What’s random reinforcement? Imagine a rat presses on a lever to get food. If every 100 times the rat presses, they get food. That’s exciting. But if it’s a random number between one and 200, the rat is more excited. The rat keeps on pressing for longer, even when the reward stops. And if you think about this metaphor of random reinforcement, it’s of course how gambling works.

Crypto has huge variance, huge reward, and punishment. And because of that, it’s very easy to get addicted. Now, it is true that if you look historically at Bitcoin, it has been doing very well. But will it continue to go up? I am not sure and I wouldn’t take that risk, personally. I would just keep a tiny amount of money in crypto as an interesting topic, but I wouldn’t keep any real stake in my future in it. I think it’s just gambling.

Human nature is inherently irrational, but you need to make rational decisions to succeed in the market. So how does one marry the

two emotions?

In an overly simplistic way, we have two types of decisions that we make—it’s about spending now versus spending later. The latter is also called savings. The reality is, for most people, saving is what we have after we finish spending. But that’s not the right thing to do. If we basically say we’ll save whatever we don’t spend, we’ll end up spending too much and not save enough. And then the sad thing is when we get to age 65, we’ll wake up and say we made a mistake. I think the Indian culture still has a huge benefit, which is that kids still respect their parents. But if your retirement strategy is not about your kids taking care of you, start working on it.

The first thing we need to do is to curb our irrational needs. That’s because ‘the now’ is very clear, but ‘the later’ is very abstract. Let me give you an example. Imagine I said, what would you rather have: a half a box of chocolates right now or a full box of chocolate in a week? And I would show you the chocolate. I would open the box, and you can smell it. Most people would say give me half a box of chocolates right now. But what if we push the choice to the future and say, what would you rather have: a half a box of chocolates in a year or a full box of chocolates in a year and a week? Most people would say, of course I can wait a week for another half a box of chocolates.

The two problems are equivalent. The difference is that the first one has emotions. When we have chocolates now, it is emotional. Chocolate in a week is not. Half a box of chocolates in a year is not emotional.

Our modern capitalistic society is a society of temptation. Every app wants you to spend your time, attention and money. Every store wants you to buy something. Now, we are walking in a world in which everybody wants something from us. Who is helping us to think about our long-term future? Maybe a spouse, maybe parents, maybe religion, maybe the government, but very little. We can say the first big failure is to do too many things that are good for us now and sacrifice the future.

So, what can we do about it? The first thing is, of course, to realise this. The second is to create a rule for ourselves. For instance, recognising that we need much more money for retirement and then create a rule.

Say, I want to save 20 per cent, or 25 per cent or 18 per cent. We have to decide what’s our rule. It’s okay to say I want to save 20 per cent, but it will take me three years to get there. I’m going to start with 10, and every year I’ll increase it by 3 per cent. Now things (monetary transactions) can be done automatically, and that will be the next thing we need to do.

You’ve dealt with various emotions and themes in your work—misbelief, dishonesty, motivation, and so on. Another emotion, you’ve dealt with in your recent blog, is mistakes. Could you tell us about people’s reaction to mistakes, such as in the stock market?

I think the stock market is a great metaphor for how we should think about mistakes. Every investor would tell you it’s about diversification. You would say I’m not smart enough to understand which stocks will go up and which will go down, and because of that I need to diversify. If I was very smart, I would just pick the best stock in the market but I’m not that smart. If you take the introductory course to finance, the first rule is don’t think you’re smarter than the market, think you’re slightly smarter and diversify. And diversification basically means we’ll make mistakes.

We live in a society where people are overly afraid of mistakes, and I think we need the wisdom from the markets, which is to basically say, let’s admit that we don’t know that much. Let’s admit that we need to gamble more, let’s try more, and let’s develop a better attitude towards mistakes.

One philosophy of life I believe in is karma. For me, karma is the law of cause and effect and it basically says we are responsible to produce good things in the world. Will the world always take it and make something good with it? No, but it is our responsibility to produce good work.

In the stock market, it means our responsibility is to put money in saving, in investing. Would it always go up? No. Our responsibility is to do the right thing and it’s very important to say… that I want to make sure I’m doing my part. And then there’s what the world is doing with it. Sometimes it’s going to take something good with it and turn it into something bad. Sometimes the opposite. But we need to figure out about what are the things that we control. And in the domain we’ve been talking about, we control what we spend money on, we control how much we put in savings. We can control how much we get better at this over time. We can control that we don’t spend on things that don’t give us enough happiness and so on. But I would say. figure out the things you can control and try to get better at that. Don’t wait for the world to do its thing.

nidhi@outlookindia.com