You are often called the Big Bear of Dalal Street. Do you identify with that?

India is a strange market. If one has been negative for a period of time, even if it is very short, one somehow gets branded as the Big Bear; and if somebody’s been bullish, you are called the Big Bull.

These are very superficial terms. In India, in particular, nobody has ever been vocally bearish at any point in time. Somehow the popular culture is that we are always supposed to say good things about markets, and never say anything remotely negative. If you say that, you are a bear.

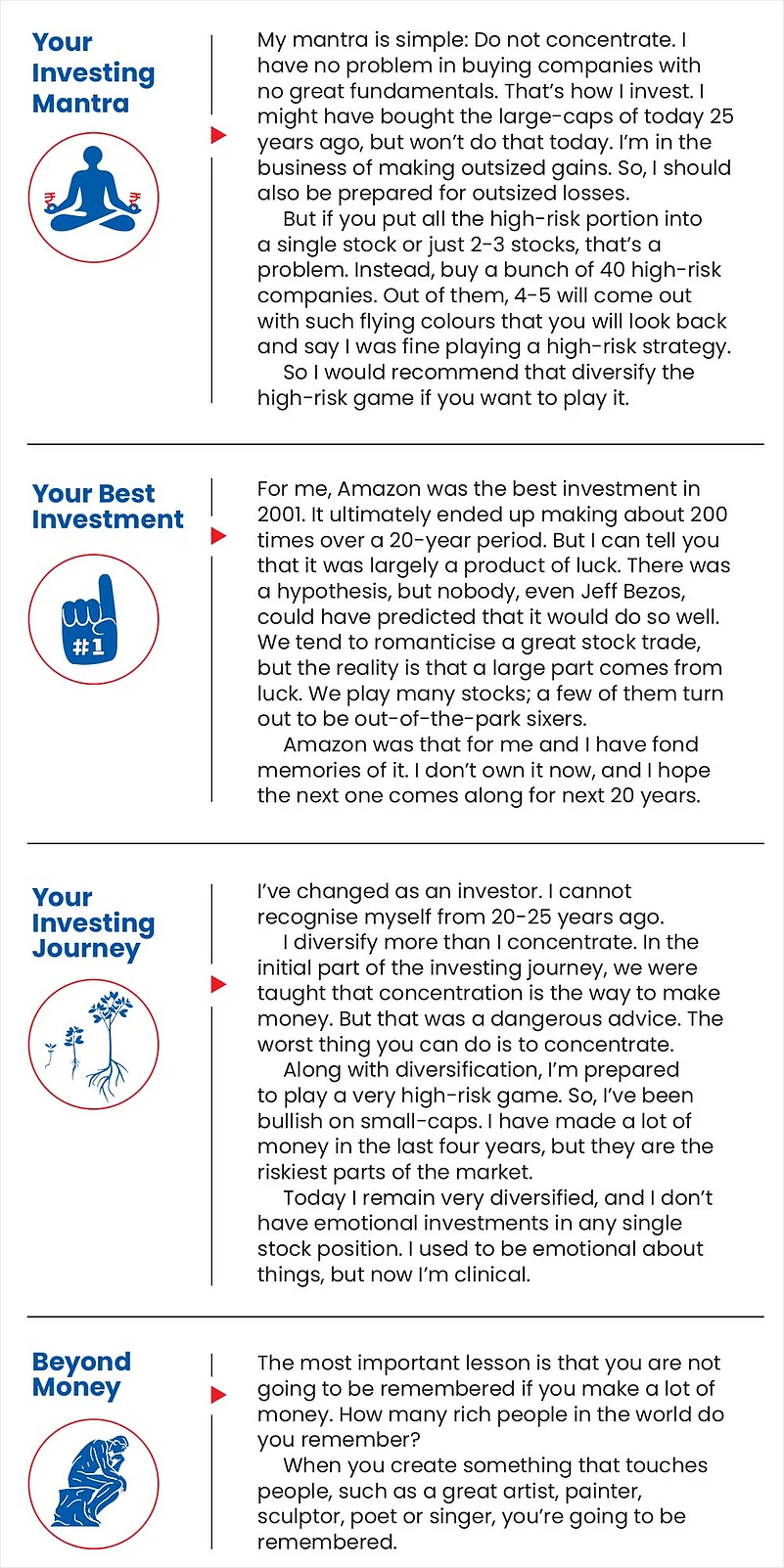

My style of investing is that I keep a very open mind. I’ve been investing globally for the last 25 years and the culture I am used to is (the one prevalent) in the US. For example, (in the US) major hedge fund managers, mutual fund managers and commentators can be openly negative about markets at different points in time, and they have been. They bet based on that view; they will go short on the market or treasury or a bunch of stocks.

That’s a very developed way of thinking—that markets go up, and they can come down as well. It’s not that markets are permanently trending upward; they do over a 30-40-year period, particularly in India or the US, but in the interim, there can be very brutal periods when you can lose literally 20-50 per cent of your capital. The interesting thing is that we have again forgotten in the last four years that from 2014 till 2020 up until Covid, the market returns from India were less than bank fixed deposit returns.

For small-caps, the less said the better. From 2018 to 2020, it was a brutal small-cap bear market, in which stocks basically got decimated by 50-90 per cent. We are just living in the good times, and we kind of believe that anything which is remotely bearish is not possible.

That tag stuck because I was bearish, but only twice, in 2000 and 2008. But believe me, I have made more money being bullish than being bearish, but being bearish has saved me a lot of money, particularly during those massive falls. So being bearish at the right point is very strategic. It is not about making money. It is about saving the money that you have made.

"In India, nobody has ever been vocally bearish. Somehow, the popular culture is that we should always say good things about the market"

Right now, the markets are on a high. Do you think investors should be cautious in these times?

So, (when you are in the market) you should always be careful. Stock markets are basically about risk. Today we are sitting in the fifth year of a bull market.

When you enter the fifth year of a bull market, statistically, most markets tend to start to correct or wobble or become somewhat nervous. That’s because markets have run up so fast for such a long period of time that they usually take a bit of a breather. I’m not saying it will happen today, but I would be circumspect in my decision-making today than in 2020, when we were coming out of a six-year bear market. When the market started to rally, I was clear that this is going to last for a few years because, importantly, the length of a bull market is directly correlated with the length of the preceding bear market.

That view came out right. The fifth year of the bull market will not be as smooth a ride as we have seen in the last four years.

Earlier this year, you said that overvalued stocks may fall 90 per cent when there’s a bear market. Do you still hold that view?

Absolutely. I have seen markets for a very long time, and in a bear market, two kinds of stocks fall. The first are stocks with a lot of leverage, like in infrastructure and construction companies.

Second, when, instead of debt capital, a company has excess equity capital, which they raise in the bull market, but find no good use for it. That’s wise, but up to a point. When you take too much capital—and many smaller companies, in particular, have been taking a lot of capital because that’s available—that capital is usually frittered away in doing silly things, or at least it does not earn a decent rate of return.

These companies get hurt in a bear market; they can be decimated 70-80 per cent. Too much equity is as bad as having too much debt.

These are mostly small-caps and mid-caps, right?

A large part of the fundraising, and the euphoria has been centered around small-caps. Large-caps haven’t rallied in any meaningful way. They have obviously gone up, but nothing compared to what the small-caps have done, and if that is indeed the situation, then over capitalisation gets centered around small-caps. Also, remember that in order to become large-caps, small-caps have to raise money. They need money, but the question is how much. It’s like exercise, medicine, sleep, everything has got a certain ratio in your life. If you have too much of any, it’s a problem. I’m not saying don’t raise capital, but don’t raise so much capital that you become profligate with capital.

Investors are still pumping money. Is this a cause for concern, especially because recently companies’ growth has been muted?

One concern that I have is that numbers this quarter have not been super good in many companies—large-, mid- and small-caps. I don’t know whether that is indicative of a generalised slowdown, as I come across conflicting views. So I’ve still not made up my mind whether it is structural, or is it just a blip, but that is a fly in the ointment.

The second point is that we are now in a situation wherein the government has proclaimed that they are going to reduce the fiscal deficit. Once the fiscal deficit starts to ratchet down, growth will inevitably slow down. One view I have heard from informed (sources) is that this year the gross domestic product (GDP) numbers could disappoint. We may end up with something under 7 per cent.

GDP numbers coming down to, say, 6.9 per cent from 7.2 per cent can be viewed negatively. But I have a caveat on this. GDP numbers hurt large companies more than small companies because they are driven by the big headline numbers. Small companies deal with smaller areas, and are not necessarily directly exposed to the macros.

"We need capital formation and we need to encourage retail investors to stay in the market. All of that is incentivised by moderate tax rates"

You mentioned a five-year period for a bull run, and with the concerns above, when do you predict the bear market will hit us?

I don’t see conditions that lead to a bear market because bear markets necessarily follow a giant bubble. The only bubble you can argue is in the small-cap, small-and-medium enterprises (SME) and initial public offering (IPO) spaces. Other than that, I don’t see a generalised bubble. What you will get is a moderation, not a collapse. Moderation cannot be called a bear market. You might have a 10-20 per cent decline in the market. I don’t call that a bear market and particularly in a country like India. If it’s 30-40 per cent lower, then it will be called a bear market. But I don’t think that’s happening anytime soon.

You’ve also pointed out that the revised capital gains tax rules may create hurdles and could accelerate the journey towards a bear market. After the Budget there was tinkering in the capital gains taxation for real estate, and tax reforms are also on the anvil. How do you see it?

I’ve been against increases in capital gains tax in equities for the simple reason that I believe it is a risky asset. The government seems to believe that it’s super easy to make money in the stock market, and I think they have got carried away by that belief. This is a mistaken notion. Stock markets are volatile animals, plus we still need a lot of capital attracted to the stock market. Both factors require moderate tax rates. An increase from 10 per cent to 12.5 per cent is a 25 per cent rise (in long-term capital gains tax).

The fact is we need capital formation and we need to encourage retail investors to stay in the markets. All of that is incentivised by moderate tax rates. So I have been against it and continue to be so. I hope they will revisit it some time.

If the government is thinking that gains come easily in the stock market, could that make retail investors reckless?

The nature of investing is that we always become reckless in elevated bull markets. That’s human nature. I’ve seen many such situations, and I’m not surprised by it. But this will pass. People will get hurt, especially people buying IPOs of companies with two dealerships and stuff like that. But I don’t see why that should be a big problem. This is a market that is buyer beware! If I buy a stock and the stock goes down, that’s my money, and I should be prepared to witness those situations. The only guy you can blame is your advisor, if he/she advised you to put money in XYZ stock. If you just saw a news report and did it, too bad. We’ve all made mistakes, and that’s part of the learning process.

Do you think retail investors are smart enough to recognise bear and bull markets? How can they be protected because awareness is still the key issue?

The only thing you can ask for protection from is outright fraud. If you are at sea, please find your methods of swimming safely. Don’t just hope that the lifeguard is going to save you if you are going to be swimming way out of your depth. If you’re out of your depth, get back to the shore or get a safety tube. But if you don’t do that and drown, don’t end up blaming the world for it.

Among retail investors, the biggest flaw is that they will find someone to blame than accept their own mistake. We all make mistakes. I have made mistakes many times, and I will continue to make mistakes. The point is, I don’t blame anybody. I bite the bullet, I learn from it, and then I put it away. It’s gone.

Our markets are very democratic and transparent. It’s a privilege to have been born in India and being blessed with a stock market as good as this.