Ask yourself, are you impatient? Do you fail to stick to your plans and New Year resolutions? Do you worry about your social status and public image? Are you a spender or a saver?

If your answer to the first three questions is yes, then it is more likely that your answer to the last question would be a spender. Here, a spender refers to a person who overspends today, which may have adverse long-term consequences on their material wellbeing, and hence their welfare.

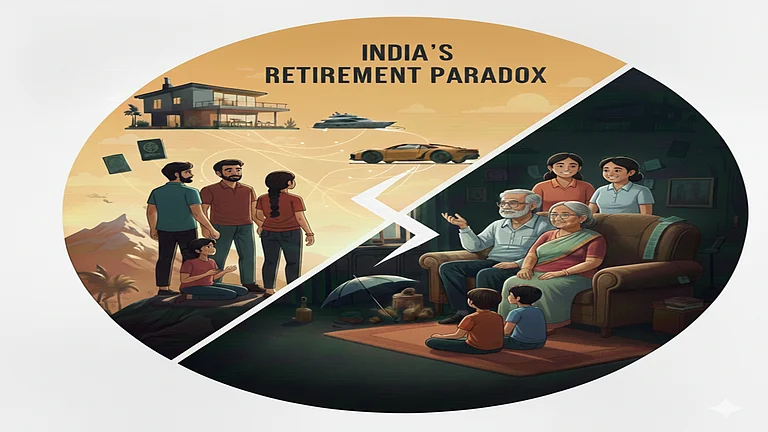

Saving enough, investing smartly, and building a large enough pool of retirement funds during our working age years is important, especially given the increase in human longevity and the rising costs of living. It is equally important to save in order to realise our dreams, such as owning a home, educating children, vacations, etc. Saving, however, is hard because it involves sacrificing consumption today. How we value costs and benefits of our decisions that occur today, versus those that occur in the future, predicts spending and saving behaviour.

How do the above questions relate to our consumption and saving habits? Take the first trait — impatience. According to the Cambridge dictionary, impatience is ‘a feeling of something wanting to happen as soon as possible’. In the case of spending, it is the inability to delay short-run gratification. Today’s enjoyment gives us higher utility than future returns — which is as present bias in academic literature.

Take the example of the launch of the latest cellphone. You begin to receive social media and email notifications from the company. Amazon begins to recommend it to you, pinpointing new features. It shows alternative purchase options, including spreading the cost of purchase over several months by opting for an EMI at 0% interest. It says it’s a limited period offer. Your current mobile is working just fine and you had no intention of buying a new model. The latest version is expensive and you figure out that the new features are not worth the price premium. It is, however, extremely tempting. How often do you fall for such an advertisement?

Now, to add to your dilemma, your friend calls you up. He is in awe of the latest cellphone, has purchased it already, and says it’s a must buy. Do you give in and make the purchase?

Why do many of us end up paying a luxury premium when we either don’t need the product or have cheaper, functionally equivalent products available? Many of us end up buying products that help us avoid social embarrassment, especially if we want to minimise risk of social rejection and comply with societal norms?

Now suppose a friend does not call you singing praises of the new product, but you still give in to make the purchase? What may have happened? Are we the friend himself, who was signalling his social status via the proclamation as proud owner of the latest model? An American economist, Thorstein Veblen, suggested in 1899 in his book, the Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions that “in order to gain and hold the esteem of men, it is not sufficient merely to possess wealth or power. The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence”. A person’s income is not generally noticeable in everyday social interactions to allow people to make status valuations. Hence, in their desire to signal social status, people are willing to pay a higher price.

Even if short of cash, people are increasingly getting worried about their public image. They borrow and splurge on acquisition of goods and services, including tonnes of unnecessary clothes. For such individuals, status products are means of enhancing their public image in front of others, as these products act as cues to their social standing. A large number of empirical studies have confirmed this.

So finally, we end up buying the product — either out of the inability to delay gratification or due to fear of social rejection, or even to signal our social status. We promise ourselves we won’t make such a hasty purchase decision again. We do mean it. But alas, when time comes to make such a decision comes again, our resolve evaporates again and again. Such behaviour is known as a ‘naïve present bias’ — we do have intentions of spending less, repaying credit card debt, exercising more and following a diet, but we fail to follow up on our well-meaning intentions.

Going back to where we started — impatience can also interfere directly with our ability to stick to our savings plan, especially in the current environment when deposit interest rates are paltry. Suppose we open a recurring deposit for a year, as well as a 1- year FD. At the end of the year, with an interest rate of 6%, we realise we have earned less in interest than the amount by which prices have risen. We wonder, what is the point of saving? Why not at least spend and have the satisfaction of being the proud owner of a product you had long eyed for?

Instead, could we not think of alternative savings instruments — where we can invest to get higher returns? If not, should we at least stick to a longer duration fixed deposit?

That brings us back to square one. To start upon a journey of saving discipline, one has to first judge whether they identify as a spender or a saver. Only then, can one take remedial steps.

The author is Professor of Economics at Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai

DISCLAIMER: Views expressed are the author’s own, and Outlook Money does not necessarily subscribe to them. Outlook Money shall not be responsible for any damage caused to any person/organisation directly or indirectly.