Meir Statman, the Glenn Klimek Professor of Finance, Leavey School of Business, Santa Clara University, California, is the second generation of behavioural finance experts who refused to label people as “irrational” and instead called them “normal”. In his latest book, A Wealth of Well-Being: A Holistic Approach to Behavioral Finance, he expands the circle of finance to include life well-being and shows how they are inextricably intertwined. As part of an interview series, ‘Wealth Wizards: Money Maestros in conversation with Nidhi Sinha, Editor, Outlook Money’, Statman spoke about his research, and explained concepts through anecdotes that can help you take balanced decisions. Edited excerpts:

Behavioural finance was a subject of much debate in its early days. Can you tell us about your experience?

I came to Santa Clara University at the beginning of 1980 and met Hersh Shefrin (Canadian economist who worked in behavioural finance), who was working on issues of saving, self-control and mental accounting, and framing that in the context of savings.

As I was listening to him, it thought that in that framework, we can understand the issue of dividends. Why is it that people care about getting dividends rather than creating what (Nobel laureate) Miller Modigliani called homemade dividends by just selling shares? What people do is use dividends as a self-control device. If they spend the shares, they think they might sell too many and not save enough. So, people constrain themselves and spend from dividends and income, but don’t dip into the capital.

Hersh and I then wrote a paper and sent it to a top journal in finance, The Journal of Financial Economics. We didn’t expect it to be accepted because it was so different, but we were fortunate that the referee was Fischer Sheffey Black (American economist, best known as one of the authors of the Black–Scholes equation), who loved the paper. The editor, despite his misgivings, chose to publish it.

Of course, there were objections. One of my colleagues said that I like the paper, but I cannot teach it to my students because it’s not rational.

I went on because there were so many things that could make sense and could be explained (through that).

So, instead of asking if it’s rational or irrational, the question is: do people do that and why do they do that? That was the beginning.

Earlier people hesitated to join, and I thought that was good because they were just leaving the entire field to me, and I didn’t have to rush. Now, of course, it is everywhere.

What kept you going?

I think if you’re going to be a professor and pursue scholarship, you might as well do stuff that is interesting to you, something you think is really making a contribution.

In fact, when I completed my studies at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, I got a job as a financial analyst. After a few months, I realised it’s not interesting to me. Yes, I earned money and if I stayed there, I would have a pension, but I thought I’m going to have a miserable life. This is why I came to the US for my PhD. I did standard finance because I was concerned about tenure and all, but soon I discovered my passion for what we now call behavioural finance. At that time, there was no such thing as behavioural finance. We did stuff that was funny to most people in finance.

You have talked about the second and third generation of behavioural economists. How are they different?

The scholarship in behavioural finance is still centered on the findings of what I call the first generation. They often described people as irrational. They moved from standard finance, where people are described as rational. Rational people care only about maximising their wealth, and they are free of cognitive and emotional errors that distract them from getting there. For example, rational people don’t trade too much.

Daniel Kahneman (Nobel winning psychologist), who passed away recently, wrote in his book that he cringes when he hears that he and Amos Tversky (Israeli cognitive psychologist) prove that people are irrational. Irrational people are crazy. This is not what people are.

I chose to call people normal. People are generally knowledgeable. Normal people are not stupid. Yes, they are sometimes ignorant and often make mistakes. But normal people can learn from those mistakes.

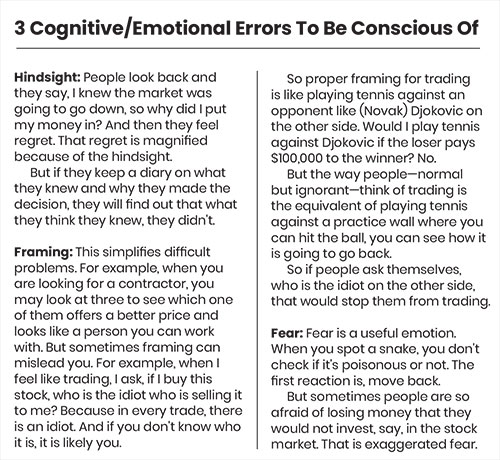

I think that people who write about behavioural finance are still fascinated by the notion that people make cognitive and emotional errors. But that is not the end of it.

So, for the second generation, as I describe it, people are normal. And people want more than utilitarian benefits of wealth. They also want expressive and emotional benefits.

I started working on socially responsible investing in the 1980s because, to me, that was a perfect example of people who care about being true to their values—for example, protecting the environment.

Often, people are willing to sacrifice some utilitarian benefits to achieve expressive and emotional benefits. We all do that. That is why we contribute to charity. Of course, we diminish our wealth, but then we get that satisfaction—the expressive and emotional benefit to say that we are good, decent people who help others.

When we talk about providing for our families, that is a utilitarian benefit because we pay for feeding and educating our children, and so on. But I also take pride in being a good father and being able to provide for my family and children.

When we see how normal we ourselves are, how can we pretend that we are rational people who care only about wealth.

So, when you call people normal instead of rational or irrational, are you being more empathetic towards humans?

Absolutely. You must be empathetic towards yourself, and other people. Every person and family have points of pain. But there are many aspects of life well-being. Finances, of course, is very important but we also have family, friends, health, education, work, religion, society, and so on. All these things either add to our life well-being or detract from it.

There are families, I imagine, where all those domains are perfect. My family is not perfect, and we support our older daughter, who has mental health issues. The way I see it is that we have injuries in some domains of life well-being, and we use resources from other domains to heal those injuries. In our case, given that we have plenty of money, we can support our older daughter without constraining our own budget.

When I disclose our pains to people, they disclose theirs, and we end up empathising with and comforting each other and enhancing the well-being of each other.

Your latest book, A Wealth of Well-Being: A Holistic Approach to Behavioral Finance, is out. How has the journey between your earlier groundbreaking book, Finance for Normal People: How Investors and Markets Behave, and this one been?

In Finance For Normal People, I said people care not just about wealth and utilitarian benefits, but also for expressive and emotional benefits.

In this new book, I expand that circle of finance to say we care about more than financial well-being; we care about life well-being. Of course, finances are important by themselves.

I see family, friends, health, education, religion and other factors like a portfolio. In a portfolio, some stocks are up, some are down, but eventually it is the total that matters. So, it’s life well-being that matters.

I took scientific literature about well-being and coupled it with stories that bring life to it. There are lots of people who work on issues of well-being such as economists, sociologists, psychologists, who know nothing about finance; and there are lots of people in finance who know nothing about well-being.

I combine scientific literature with stories that I get from India, China, Mexico and other countries, to get a sense that people everywhere strive to gain life well-being.

Could you tell us about some of the stories from India?

I will talk about one aspect of India that I know. I have colleagues and neighbours who are originally from India. A lot of families from India want to get their kids into top Ivy League colleges. In fact, I found that there is one Indian city where there are cram schools that prepare people to apply to top universities, and most don’t make it. Some of them may be children of labourers, small businessmen and people who may not be highly educated themselves, but they want their kids to go to top universities. And it sort of breaks your heart. Our neighbours tell us that it matters a lot in India, not just in terms of expressive and emotional benefits, but also in terms of money as it may open doors (to money).

The US is different. As long as you graduate from a college, even if it is not among the top ones, you are likely to do well. In fact, it turns out that you don’t earn much more, on average, if you graduate from an Ivy League college compared to a smaller college. So, you can be an owner of a plumbing business, and can earn a lot more than a university professor.

To some extent, the desire to send your kids to the top university has to do with culture. But Indians in the US are adapting to the new culture. There are many parents who are graduates of top universities in India or the US, and they really try consciously to take their foot off the accelerator a bit.

How does education play a role in life well-being?

Education brings knowledge and critical thinking that is useful in gaining employment. But it does more than that. For example, universities also serve as what economists call a marriage market.

There’s actually an interesting story about that. In the old days in the US, men with high income were in greater demand than people who were, say, manual labourers. Now, when you look at the US matrimonial ads and sites where people meet, people say things about personality, and don’t mention money. But in India, people are still quite open that they are looking for people of a particular caste and a particular level of income and so on, and they’re not shy about it.

Of course, money matters in the US as much as in India. But maybe it’s part of the cultural capital in the US to not talk about that openly.

Coming back to universities, there was a famous letter by a Princeton student, who graduated two or three decades earlier, in the student newspaper, where she wrote that eventually what matters to women is finding a man who is a high earner. She said you have a selection of men who are worthy of you, so find a husband before you graduate.

There is another story about a couple, who are Princeton graduates. The woman thought that with equivalent education and skills, neither of them will have to work killer jobs. But both of them working those killer jobs. She realised that her husband would not leave his high-stress, high-income job, so she left the job and became a homemaker. So even in the US, those stereotypes of the husband earning money, and wives maybe working part time or in a lower-stress job or just being a homemaker is very common.

Though we won’t like to admit it, marriages where wives earn more than husbands many times work perfectly well but, on average, they are less stable than marriages where husbands earn more than the wives.

In your book, you have talked about four capitals—cultural, social, personal and financial. Could you elaborate?

Cultural capital has to do with knowledge of the culture that you are in and other cultures as well, so that you feel comfortable in it.

When I came to the US from Israel, I did not have the cultural capital of Americans, and so I had to learn from my mistakes. I told my classmates, ‘If you hear me mispronounce a word or mangle a sentence, even if you understand what it is that I meant, stop and tell me so that I will know’. I felt like an anthropologist trying to make sense of the natives.

So, if you go for a job interview, and meet people from a particular culture, not knowing simple things like which utensils to use for fish and for meat, can make you uncomfortable.

Social capital has to do with who are your friends, the people you can rely on and who can rely on you. Among the working class in the US, family is at the centre of social capital. So, you can rely on your brother to maybe borrow money if you need.

Among the elites, family is still central, but we tend to have more of those friendships where there is somebody we know professionally and can ask them for a reference for a job.

To understand personal capital, think about beauty. People who are more beautiful have more friends, they are more attractive to those of the opposite sex, and so on. Their life well-being is higher. And then there's personality. There are optimistic people who tend to enjoy life more than people who are always thinking about the half empty glass.

Some of those things we can change, but not all. We just have to understand it and live within those constraints. Of course, financial capital matters a great deal.

People behave and respond to different situations differently. But with robo advisory making inroads, how will things will pan out?

I am on the advisory board of one of the robo advisors so I know how they work. They try to bypass the human advisor, and they are much less expensive. But the comparative advantage of human advisors is in creating a human connection. It’s like when you go to a physician, you expect him or her to know how to diagnose and prescribe, but you also expect the physician to make you comfortable, so that you can disclose even things that are embarrassing.

There are things about our wealth that are embarrassing that we don’t talk about in company. Human advisors can’t compete on lower fees or on constructing perfect portfolios, but they can compete on the relationship they form with clients.

For example, one advisor told me about a couple that came to him, and told him that they had a disabled son, and their plan had to be such that he was taken care of long after they were gone. So, here’s a case where a client discloses the pain, and you can help them. Of course, there is the financial aspect. It's not just a matter of empathy but also about maybe creating a trust fund to help that child.

Then there are some parents who are very wealthy and are reluctant to give their adult children money because they’re afraid that they will lose their initiative to become successful. But people in their 20s are very poor as they are just beginning their careers, and this is when they need help. They don’t need help when we die at 95 and our children are 65.

In this sense, many Americans are very different from Israelis. When Navah, my wife of more than 50 years, and I were about to be married, we had dinner with our parents, and then we were excused to go for a walk. Our parents sat down to business, which meant how much each pair of parents is going to give the young couple to get them started on a down payment of a house. It was in fact not a surprise. So, you can see, how finances, family, culture, all interact.

Robo advisory may not give in to desires? Is that useful?

That’s true. Human advisors may empathise with their clients too much. So, they may allow investment in hedge funds. Lots of people want to invest in these for the snob effect, for expressive and emotional benefits. But robo advisors design portfolios that are not bent towards desires that may not always be wise. So, that’s useful.

Human advisors can do the same. What you need is an advisor who is empathetic but is able to say that if you continue spending this way, you’re going to be bankrupt soon.

nidhi@outlookindia.com