Calculating a retirement corpus on the basis of average returns can have disastrous consequences as different sequence of returns can lead to different outcomes

How Averages Can Ruin The Retirement Math

Calculating a retirement corpus on the basis of average returns can have disastrous consequences as different sequence of returns can lead to different outcomes

It’s 1996, and after a long and fulfilling career, Shalini is looking forward to her retirement in a couple of weeks. After having worked hard and accumulating a good retirement corpus, she is keen on spending the next many years in leisure.

Shalini is grateful that her retirement has come after the tumultuous years of 1990-1991 when the Indian economy went through a crisis. Much to her relief, the economic liberalisation that followed stabilised the economy. She was hopeful for better days.

A disciplined saver, she has accumulated a retirement corpus of Rs 1 crore. This consists of a mix of Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), Public Provident Fund (PPF), fixed deposits, mutual funds and shares.

Before her official retirement date, she rang up her trusted adviser, Maya, to undertake a retirement planning exercise and Maya prepared the following analysis.

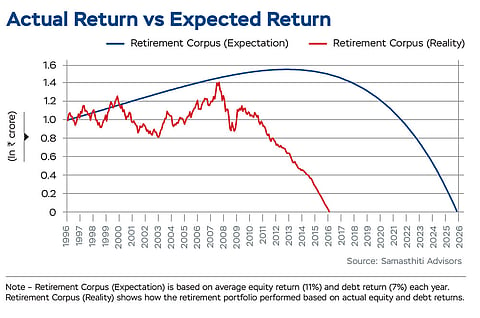

Shalini was about to turn 60. Based on family history, Maya assumes her life expectancy as 90 years. Both Shalini and Maya are aware that having a large allocation to debt investments would not be optimal as the post-tax return on these can be dismal, but some amount is needed for safety. Finally, Maya settles for an allocation of 70:30 in equity and debt.

For equity returns, she assumes an average return of 11 per cent each year, a conservative estimate, as the equity markets delivered close to double that return over the previous 15 years. Maya would always remind Shalini, “The reality should outperform the plan, and not the other way around.”

For debt investments, she assumes an average return of 7 per cent each year, assuming a 1 per cent real rate of return over the projected inflation of 6 per cent. The blended portfolio return was expected to be 9.8 per cent each year.

Maya also needs to calculate a pension amount which can be increased by the expected inflation rate of 6 per cent each year.

After adjusting the portfolio return with inflation, Shalini can draw a monthly pension of Rs 50,000 in the first year. In later years, the pension amount would increase by 6 per cent to account for inflation. Shalini is happy with the pension amount.

Maya told her that in the initial years, the corpus will grow as the income from investments will exceed the withdrawals. However, later, due to inflation, the withdrawals will outstrip the income from the portfolio. From that point onwards, Shalini will have to start consuming a part of the principal. Maya assured Shalini that even then her retirement portfolio will not exhaust before 2026.

Initially, things worked out well. But this proved to be the lull before the storm. During the dot-com bust in 2000, the markets tanked by about 50 per cent. The value of Shalini’s retirement portfolio deviated significantly from the projected value. Maya assured Shalini that when the markets recover, things will get better. Maya was right. The bull market during 2004-2007 took the retirement corpus to close to the projected value by the end of 2007.

Then came the global financial crisis in 2008, which severely hit Shalini’s corpus. Maya again assured Shalini that this time around as well, and things will slowly get better.

Unfortunately, this was not to be. In every subsequent annual review, the gap between the projected and the actual corpus grew wider. Soon, the harsh reality dawned on them that the retirement corpus would exhaust itself as early as 2016, when Shalini would be 80 years old. At a time when financial security would be Shalini’s foremost priority, she would have to grapple with the prospects of exhausting her retirement corpus a full 10 years earlier than anticipated.

So, what went wrong? Did Maya use aggressive return assumptions?

She had projected equity returns of 11 per cent each year, which was the actual equity return between 1996 and 2016. She had assumed debt returns of 7 per cent each year, which actually was close to 9.5 per cent in the same period. It’s clear that we cannot fault Maya on her return assumptions.

On closer examination, it appears that the real culprit was using averages. A typical retirement plan assumes that the investments will earn a constant average return each year. Such assumptions imply that there is no volatility in returns.

However, the reality is different as evidenced by Shalini’s case. Her equity portfolio did indeed earn 11 per cent return on average, but it did so with wild gyrations.

During market crashes, the return went down significantly below 11 per cent and during periods of recovery and growth, the return was much higher than 11 per cent. This volatility prematurely killed her retirement portfolio. The higher return on her debt investments was unable to offset the volatility in equity returns.

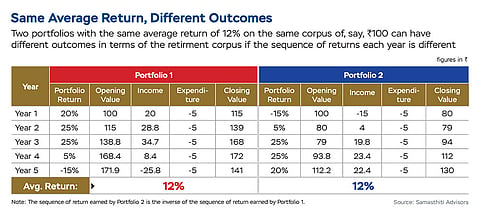

Retirement planners call this the sequence of return risk. It is important to consider not only the average return earned by a portfolio, but also the sequence in which those returns were earned. Two portfolios with the same average return can have wildly different terminal values depending on the sequence of returns earned (see Same Average Return, Different Outcomes).

A better way to design a retirement plan that incorporates the sequence of return risk is to use the concept of safe withdrawal rates. Using this approach, a planner looks at the divergent sequences and possibilities considering that a retirement portfolio will not earn the same return each year, and then arrives at a withdrawal rate that will not exhaust the portfolio prematurely.

Luckily for Shalini, she decided to sell a real estate investment, which she was planning to bequeath to her daughter, to bail her out. We may not be so lucky, which is why it’s imperative we don’t let averages fool our retirement plan.

By Ravi Saraogi, CFA, Sebi RIA and Co-founder of www.samasthiti.in